R setup

library(lattice)

library(tidyverse)

library(MASS)

library(gamlss)

library(COUNT)

library(brms)

library(rstanarm)

library(knitr)

library(kableExtra)

library(uls) # pak::pak("lsoenning/uls")December 13, 2023

One complication that arises when working with the negative binomial distribution is the fact that it can be written down in two different ways. These different parameterizations yield the same results for the mean of the distribution, i.e. the expected count or rate. Thus, if we are only interested in the occurrence rate (or normalized frequency) of an item, including a 95% statistical uncertainty interval, no problems arise. If we are interested in the negative binomial dispersion parameter, however, we must know which parameterization is implemented in the R package or R function we are using. The main purpose of this blog post is to divide R functions into two groups, depending on which version of the negative binomial distribution they use.

In general, the negative binomial (NB) probability distribution1 is spread out more widely than the Poisson distribution. It has two parameters: the mean, or expected count, \(\mu\) and the auxiliary parameter \(\phi\), which adapts to the excess variability in the data. A visual explanation of the NB distribution can be found in this blog post).

A potential source of confusion arises from the auxiliary parameter \(\phi\). This is because the NB distribution can be written down using either \(\phi\) or its reciprocal \(\frac{1}{\phi}\). Accordingly, the output of software (and different functions in R) varies, and we need to be clear about whether we are looking at \(\phi\) or \(\frac{1}{\phi}\) in the output of an analysis.

Inside of the NB distribution, the auxiliary parameter defines a gamma distribution which in turn controls how widely spread out the negative binomial distribution is. The version2 of the gamma distribution that is built into the NB distribution can be expressed using the gamma scale parameter, which is proportional to its spread: the larger the spread, the larger the scale parameter. This cognitive fit between parameter and interpretation is an attractive feature of this parameterization.

The gamma distribution can also be expressed using the gamma shape parameter, which is the reciprocal of the scale parameter. The shape parameter is therefore inversely related to the spread of the distribution, which is somewhat counterintuitive: The larger its value, the smaller the spread of the gamma distribution. We will use \(\phi\) to denote the shape parameter and \(\frac{1}{\phi}\) to denote the scale parameter:

If \(\frac{1}{\phi}\) is 0 (and, equivalently, if \(\phi\) is \(\infty\)), the NB distribution reduces to the Poisson distribution. Note that the shape parameter is sometimes also labeled \(\nu\) (e.g. Long 1997, 232; Hilbe 2011, 189) and some authors use the symbol \(\alpha\) to denote the scale parameter (Long 1997, 233; Long and Freese 2014, 508; Hilbe 2011, 189). We will use \(\phi\) and \(\frac{1}{\phi}\) to clarify the relationship between the parameter(ization)s.

Writing down the NB distribution with the scale parameter \(\frac{1}{\phi}\) is sometimes called the ‘direct parameterization’ because of the direct link between the value of the parameter and the level of spread. Using \(\phi\) instead is called the ‘indirect parameterization’. R functions and packages differ in how they parameterize the NB distribution, i.e. whether they return an estimate of \(\phi\) or \(\frac{1}{\phi}\). Table 1 gives details about a number of modeling functions in R.

| R package | Function for regression model |

|---|---|

| Direct parameterization: Scale parameter | |

| COUNT | ml.nb2() |

| gamlss | gamlss( ... , family = 'NBI') |

| Indirect parameterization: Shape parameter | |

| MASS | glm.nb() |

| brms | brm( ... , family = 'negbinomial') |

| rstanarm | stan_glm( ... , family = 'neg_binomial_2') |

# tdm <- read_tsv("C:/Users/ba4rh5/Work Folders/My Files/R projects/_lsoenning.github.io/posts/2023-11-16_negative_binomial/data/brown_tdm.tsv")

#

# str(tdm)

#

# n_tokens <- tdm[,which(colnames(tdm) == "which")]

#

#

# saveRDS(n_tokens, "C:/Users/ba4rh5/Work Folders/My Files/R projects/_lsoenning.github.io/posts/2023-11-16_negative_binomial/data/frequency_distribution_which_Brown.rds")

n_tokens <- readRDS("C:/Users/ba4rh5/Work Folders/My Files/R projects/_lsoenning.github.io/posts/2023-12-13_negative_binomial_parameterization/data/frequency_distribution_which_Brown.rds")

n_texts <- as.integer(table(n_tokens))

token_count <- as.integer(names(table(n_tokens)))

which_data <- data.frame(n_tokens)

colnames(which_data)[1] <- "n_tokens"

rm(n_tokens)We now fit an NB model to the observed frequency distribution of which in the Brown Corpus. For more background on these data, see this blog post. To obtain parameter estimates, we run a negative binomial regression model (NBRM). To keep things simple, we will assume all texts to have the same length (which is largely true).

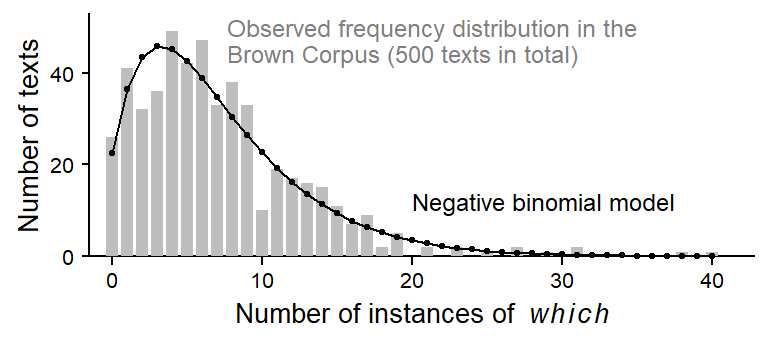

Figure 1 shows the data we are about to model: the observed frequency distribution of which in the Brown Corpus, which consists of 500 texts. The grey bars represent the distribution of token counts across texts: These vary between 0 (n = 26 texts) and 40 (1 text), and the distribution is right-skewed, which is quite typical of count variables, since they have a lower bound at 0. The black profile shows the NB distribution fitted to these data. It appears to offer a decent abstraction of the observed token distribution.

m <- gamlss(

n_tokens ~ 1,

data = which_data,

family = "NBI",

trace = FALSE)

nb_density <- dNBI(

0:40,

mu = exp(coef(m, parameter = "mu")),

sigma = exp(coef(m, parameter = "sigma")))

xyplot(

n_texts ~ token_count,

par.settings=lattice_ls, axis=axis_L, ylim=c(0, 53), xlim=c(-1.5, NA),

scales=list(y=list(at=c(0,20,40,60,80))),

type="h", lwd=6, lineend="butt", col="grey",

xlab = expression("Number of instances of "~italic(which)),

ylab="Number of texts",

panel=function(x,y,...){

panel.xyplot(x,y,...)

panel.text(x=7.7, y=47, label="Observed frequency distribution in the\nBrown Corpus (500 texts in total)",

col="grey50", cex=.9, adj=0, lineheight=.9)

panel.text(x=20, y=12, label="Negative binomial model",

col=1, cex=.9, adj=0)

panel.points(x=0:40, y=nb_density*500, pch=19, col=1, cex=.8)

panel.points(x=0:40, y=nb_density*500, pch=19, col=1, type="l")

})

ml.nb2()The COUNT package (Hilbe 2016) can fit NBRMs with the function ml.nb2(). It returns the gamma scale parameter, which is named “alpha” in the output. We can inspect the coefficients by simply typing the name of the model object (here: m). Then we could use subscripts to access the scale parameter and its standard error (here: m[2, 1:2]).

Fit the model:

Display model coefficients and their standard errors:

Estimate SE Z LCL UCL

(Intercept) 1.9633579 0.03520503 55.76924 1.8943561 2.0323598

alpha 0.4792296 0.04059087 11.80634 0.3996715 0.5587877

gamlss( ... , family = "NBI")The gamlss package (Rigby and Stasinopoulos 2005) also allows us to fit NBRMs by specifying the appropriate family, in our case family = "NBI". It returns the gamma scale parameter under the label “Sigma”, and – importantly – on the log scale. To obtain the gamma scale parameter, we therefore need to undo the log transformation, i.e. exponentiate using the R function exp(). We can use coef(m, parameter = "sigma") to extract the logged scale parameter.

Fit the model:

Display (back-transformed) gamma scale parameter:

Display standard error for the log-transformed (!) gamma scale parameter:

glm.nb()The MASS package (Venables and Ripley 2002) includes the function glm.nb() for fitting NBRMs. In the output, the gamma shape parameter is called “Theta”, and its estimate can be extracted from the model object m using the code m$theta. The standard error of the shape parameter may be obtained with m$SE.theta:

Fit the model:

Display gamma shape parameter and its standard error:

brm( ... , family = "negbinomial")The brms package (Bürkner 2017) allows us to fit a Bayesian NBRM by specifying the appropriate family, in our case family = "negbinomial". It returns the gamma shape parameter under the label “shape”.

Fit model:

Display gamma shape parameter:

stan_glm( ... , family = "neg_binomial_2")The rstanarm package (Goodrich et al. 2023) can also fit Bayesian NBRMs by specifying the appropriate family, in our case family = "neg_binomial_2". It returns the gamma shape parameter under the label “reciprocal_dispersion”.

Fit model:

Display gamma shape parameter:

For completeness, we provide the mathematical definition of the negative binomial distribution (more specifically, the NB2). The probability of a count y given x is \(\small{\Pr(y\;|\;x) = \frac{\gamma(y+\phi)}{y!\;\gamma(\phi)} \left(\frac{\phi}{\phi + \mu}\right)^{\phi} \left(\frac{\mu}{\phi + \mu}\right)^{y}}\) where \(\small{\gamma(\dots)}\) is the gamma function and \(\small{\phi}\) is the dispersion parameter. In R, we can use the function dNBI() in the package gamlss.↩︎

Don’t be confused if the way the gamma distribution is introduced here does not correspond to descriptions you find in the literature. The distribution is actually characterized by two parameters \(\small{p_1}\) and \(\small{p_2}\) (see, e.g. Gelman et al. 2013, 578–79). For the negative binomial distribution, we need a gamma distribution that is centered at 1, which makes one of these parameters (i.e. \(\small{p_1}\) or \(\small{p_2}\)) redundant. The mean, or expected value, of a gamma distribution is given by \(\small{p_1/p_2}\). In order for the mean to be 1, we have to set \(\small{p_1=p_2}\), so the version of the gamma distribution we need for the NB distribution only has one parameter.↩︎

@online{sönning2023,

author = {Sönning, Lukas},

title = {Different Parameterizations of the Negative Binomial

Distribution},

date = {2023-12-13},

url = {https://lsoenning.github.io/posts/2023-12-13_negative_binomial_parameterization/},

langid = {en}

}